Some time ago, I was appointed scriptwriter for our annual Malaysian Society performance, MNight. It's a musical made with the aim of allowing Malaysians in my university to pull off a production together, meant to be a reminder of home for our audience.

In the process of planning and writing the script, I came to realise that I don't actually know my country. I love it, unquestionably, but I don't know it.

What does it mean to be Malaysian? I have spent most of my formative years circling the idea, acknowledging the fact without exploring the nuances. In all my years in Singapore, I have always insisted on my Malaysian-ness, but somehow I never quite stopped to think about what that even meant.

The fabric of my country's makeup makes it difficult to define, but it's not impossible. I'm stretched thin across the different cultures I am part of, but this isn't a solo search.

Partially, it's the fact that my country's never quite managed to articulate itself properly. My Malaysian friends will easily name their favourite aspects of our country, but I don't believe we can bring a singular, coherent identity together. Singaporeans go through a standardised system where they emerge with shared ideas and ideals about what their country is and what it represents. It's rather vaguer for me, when our system flip-flops as it fancies and pins nothing down as truth.

It's easy for some people to say: I'm Indian. I'm Chinese. I'm American. I'm French. There's layers and depths and subsets to that too, but the overarching idea of a nation does exist, binds a community together on an international platform.

Sometimes you have to contend with more. To say I am Malaysian is never quite enough, isn’t it? It means, in full: "I'm Malaysian Chinese, but no, I'm not from China, I've never been, I don't identify with China and China most certainly does not identify with me."

What is an ethnic minority? By Malaysian definition, I am part of the three major races in my country, and yet we are a 'minority' and discriminated against the majority Malays. In Singapore, I become part of the majority and receive what has been loosely termed 'Chinese privilege', a playoff on the Western white privilege. In the West, I am too often mistaken for China Chinese. In Britain in particular, I am again part of an ethnic minority, this time with the additional weight of history from a Commonwealth country. In the US, I would be part of a 'model minority', but a minority nonetheless. In China I would be an outsider, never quite enough.

What does ethnic Chinese even mean? You could say we are Han Chinese, but even among Han Chinese there are multiple subcategories - Cantonese, Hokkien, Teochew, Hakka, etc. I am of Hakka descent, and recently I found out that Hakka people were nomads, wandering across the mainland without any real roots. Unlike Hokkien people, who would be from the Fujian province, or Cantonese people, who would usually be from Guangdong, my history traces back to a people who never stay still, who leave no traces.

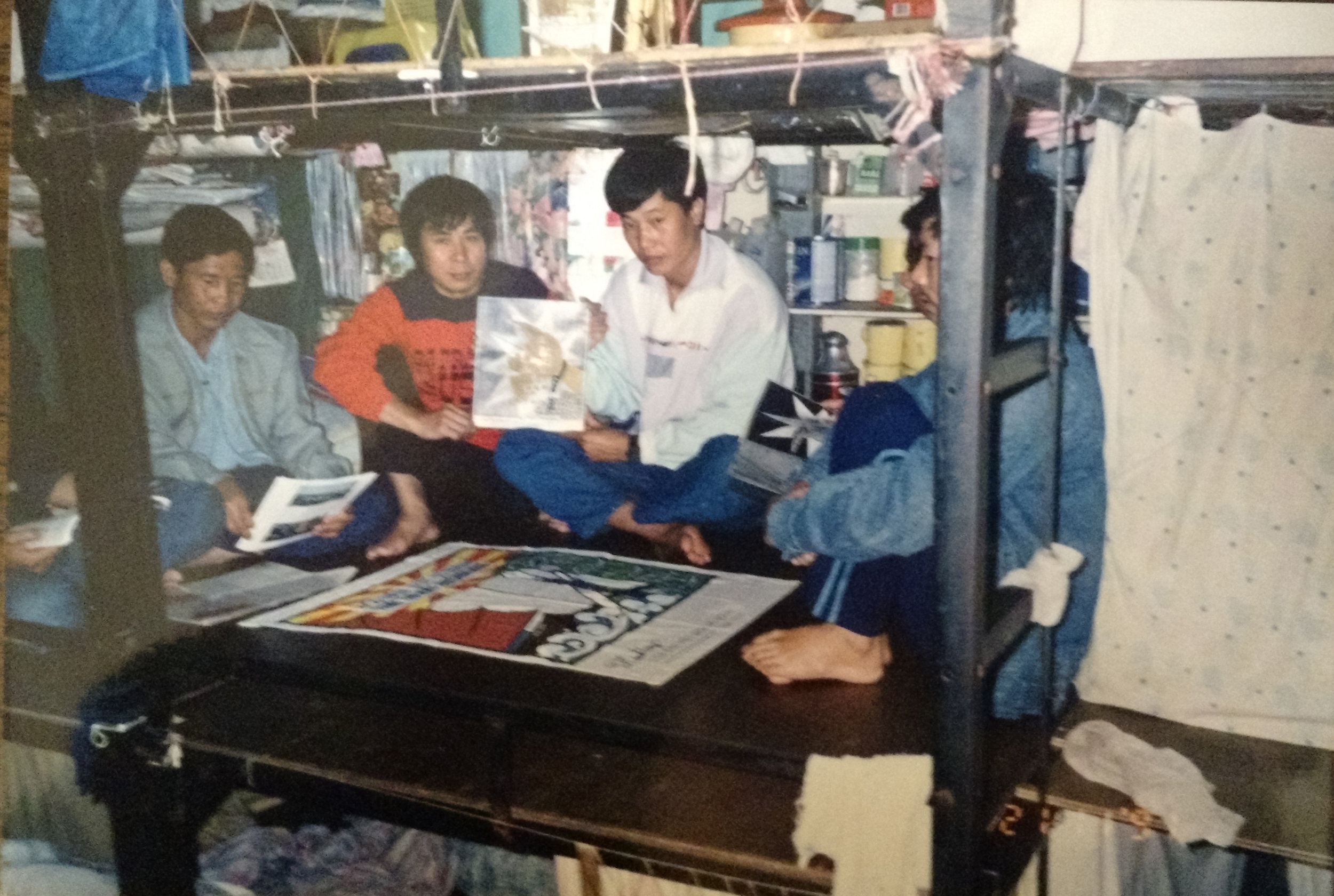

It is a strange habit of my family that my sister and I were not told stories of my parents' or grandparents' younger days. I can't help but wonder. My grandmother would have been a child at the start of World War II, and she lived through the Japanese Occupation. She saw the triumph of merdeka and the fallout with Singapore. My parents and their siblings were children during the May 13th racial riots. They grew up in the shadow of the Cold War. They were there. And beyond all these historically significant events, there is the kampung life that raised them, a reality of childhood so removed from anything I know.

Look ahead to the bright future, my grandmother used to say. Don't look back at the past, that's over and done with.

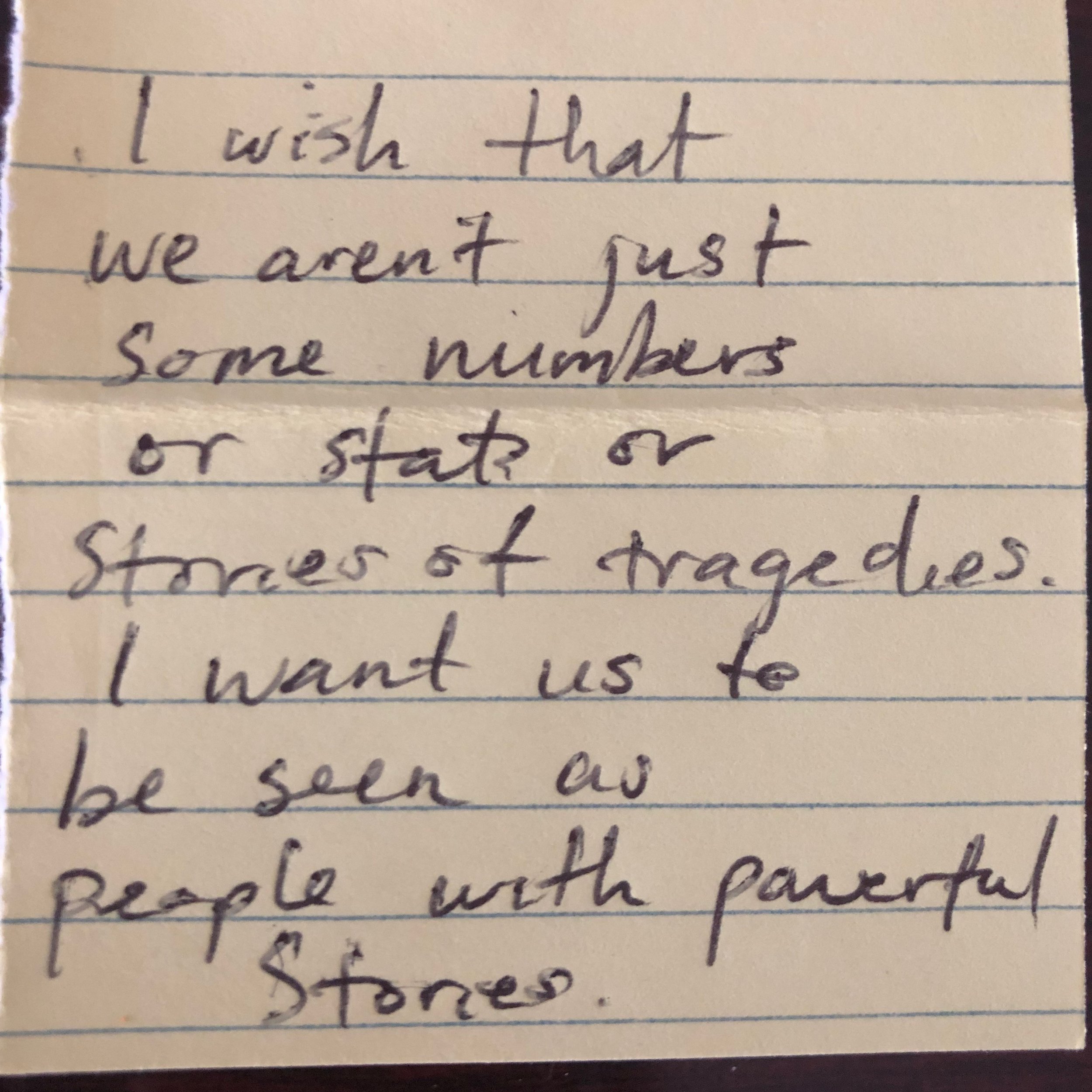

But I want to know. I always want to know. I can't say exactly why it's important, but I know that it's important that someone remembers. For someone to tell me and for me to tell others how I got here, the choices other people have made to put me where I am today, where I will make more choices that ripple out in a million different ways. I don't believe in wallowing in the past or reviving old glories, but someone ought to make sure this isn't forgotten.

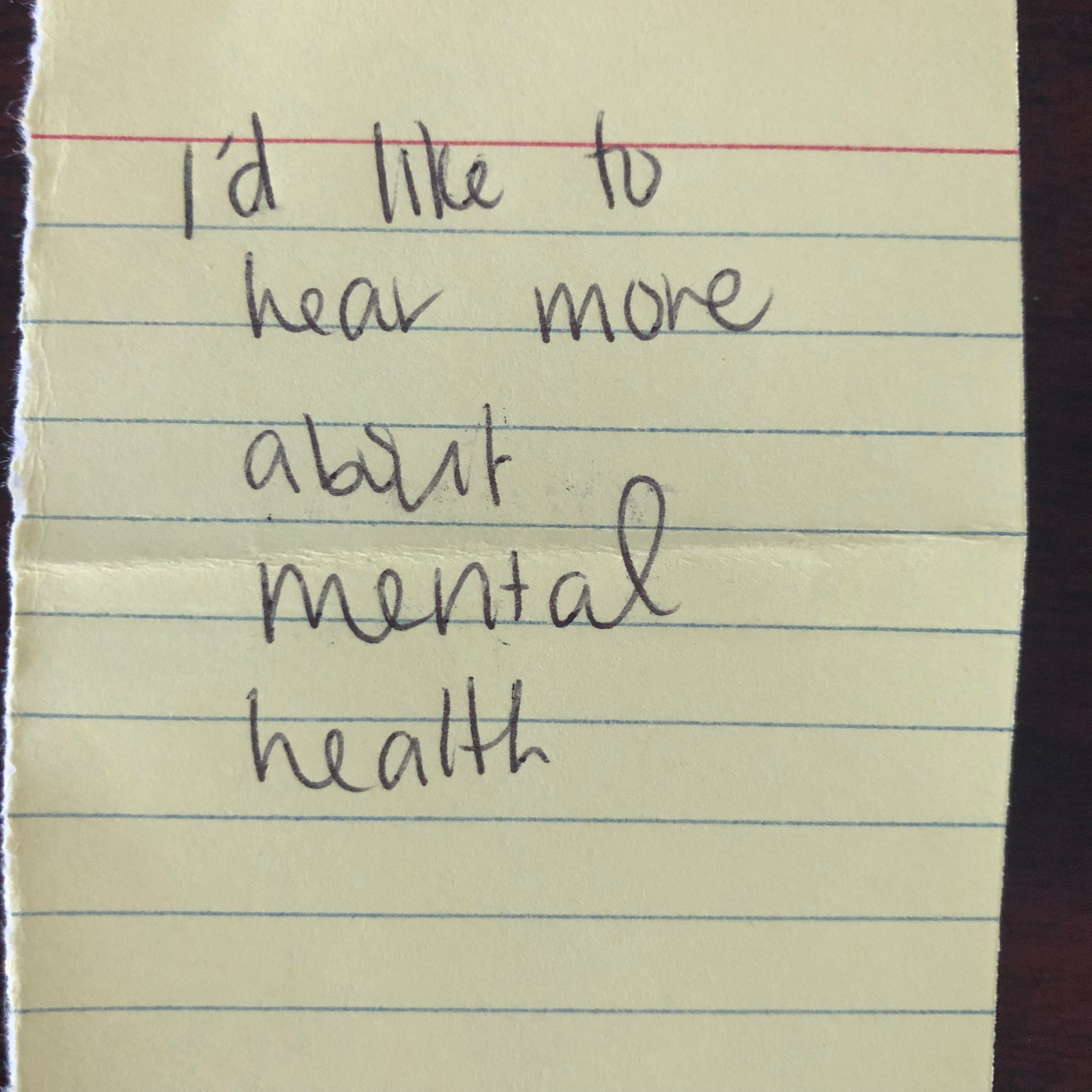

A lot of what I watch and read in entertainment and education isn't for me. It's removed. It's seen through the lens of Western media, an immigrant filter, a left-wing approach - I'm part of that, and yet not. I haven't seen much that comes from a perspective where I can say, "yes, that's exactly what I was thinking". I find it hard to relate to the way queerness is depicted and celebrated in the West; not that I don't agree with it, but that it doesn't quite resonate the same. This is uncharted territory. These are waters we have to navigate. The only way forward is the one we make ourselves. Black scholars have done much in this regard, but I am not black and my narrative is not theirs.

What does ethnic Chinese mean when you are Southeast Asian and watching the rise of the dragon? China does not claim the diaspora for its own. We do not claim China for our own either, no reminiscences of our homeland even though it is the originator, the cultural motherland. My PRC friends and I share a common culture and language, but I am not of them, and they know they are not of me.

What happens when China's might grows ever stronger? What happens to us, the ethnic Chinese who are and yet can never measure up to the 'real' Chinese of the mainland? There are one billion of them. My country barely numbers a third of that. Will we be sidelined to act as intermediates between China and ASEAN? What kind of role can we play when we claim ourselves fully Malaysian and yet our country does not recognise or value us on an equal level?

What happens to a diaspora that's not really a diaspora? China may be the historical, cultural motherland, but there is no longing to return, no sense of homecoming the way Jews have dreamed of a lost Israel or immigrants in the West think of India or Hong Kong. It is not the homeland. China's presence creeps into our countries, in architecture and economic deals and political influence, and where do the local ethnic Chinese go, when we cannot compete with them?

In the West, black people have a culture of their own, bound by a history of slavery and the pain that echoes down the generations. I think Chinese people don't quite have that yet, or at least, the diaspora does not. Chinese immigrants, whose parents fled west during the long turmoil of the 20th century, have an entirely different experience compared to us, my family and those of most people I know, who trace back at least five generations in Southeast Asia. We sank our roots in the soil here long before the axis of the world spun east. This is our earth and water.

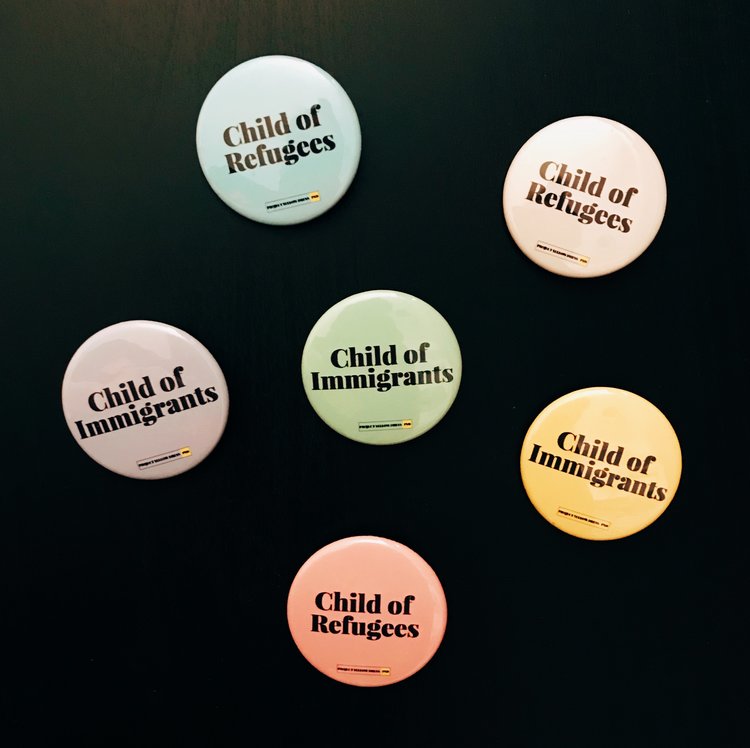

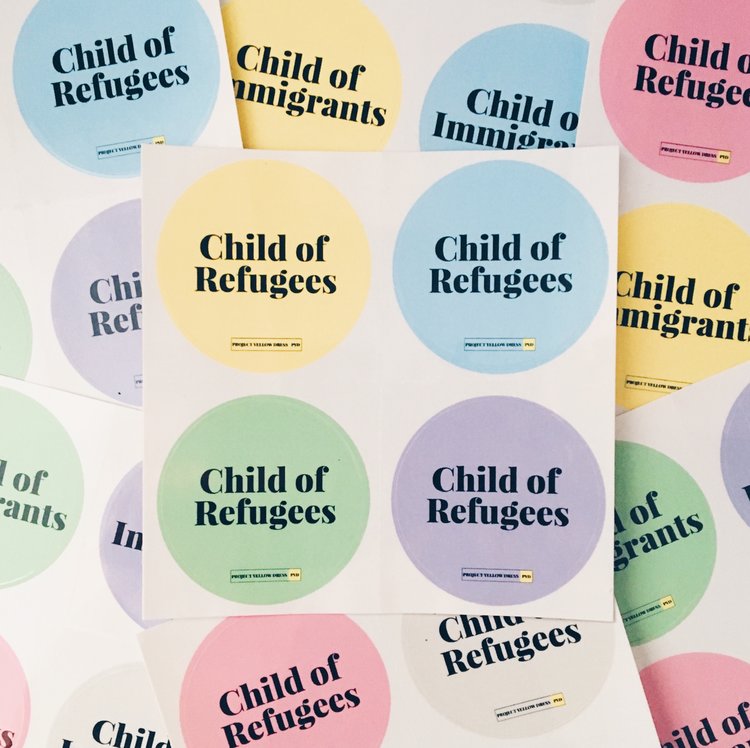

I know the Hamilton movement meant well when they claimed that we are all immigrants, but the truth is: we are not. I am not an immigrant. I was born and raised here and I am as much a part of this country as any other, even if the government does not think so. Even if I don't quite understand what it means to be Malaysian yet. To claim immigrant status is to weaken what we have fought for in this country, to concede that we are pendatang, visitors only, new arrivals, and less.

I don't claim the immigrant experience. I don't claim the experience of the mainland. I am somewhere in between, and I haven't quite figured out what that means yet.

When I speak Hokkien, the way I have learned at my mother's knee, words like tapi, pulut, suka trip out of my mouth. I say these words in the lilting accent of our northern island Penang, whose Hokkien is so different from the coarser southern version in Johor and Singapore. These are Malay words that have sneaked into the language, a mixture of dialects and customs that have found their place here. I can't tell you what the proper Hokkien equivalent of kahwin (marriage) is, how to pronounce it as it's written in proper Chinese (结婚), I only know it as kahwin - its inflection changed, but retaining essentially the same base word as the one in Malay. Our habits and languages have washed over and integrated with each other and become a shared, living thing.

As Benedict Anderson says, what is a nation but a group of people who imagine themselves a community? People have died for this. I have refused, quite ridiculously, citizenship in better countries in favour of holding true to this singular, imagined concept. Wars have been waged over this fiction of geographic borders, of lines drawn on a map. What is it but ink and paper?

The snobby academic in me sniffs and says that nationhood is an arbitrary human concept and not something that lasts, but emotion doesn't care about academic superiority.

It seems so trivial, but it also means something. It matters. It matters to people who have been run out of their homes. It matters to people who made the practical choice and left to make better lives. It matters, even if I still don't have to words to articulate precisely why. Maybe it's propaganda, maybe it's conditioning, but it's sunk its teeth in me and I can't tear it out.

I became aware of it at age twelve, I think. When I first left. It's a fragmentation, a fracturing of self. And you realise that no place or nation can love you back, no matter how much blood and tears you spill in its name. No matter what you burn, it will not burn for you. You are but a drop in the ocean and what does the ocean care about that single drop? It's not capable of love, not like that. That's how the idea of nationhood keeps you in its grip: it makes you fall in love with an ideal that can never return the force of your loyalty, can make no promises to stay and be steadfast.

It's so arbitrary. Just a passport. Just paperwork. The name of a country, one that didn't even exist a hundred years ago.

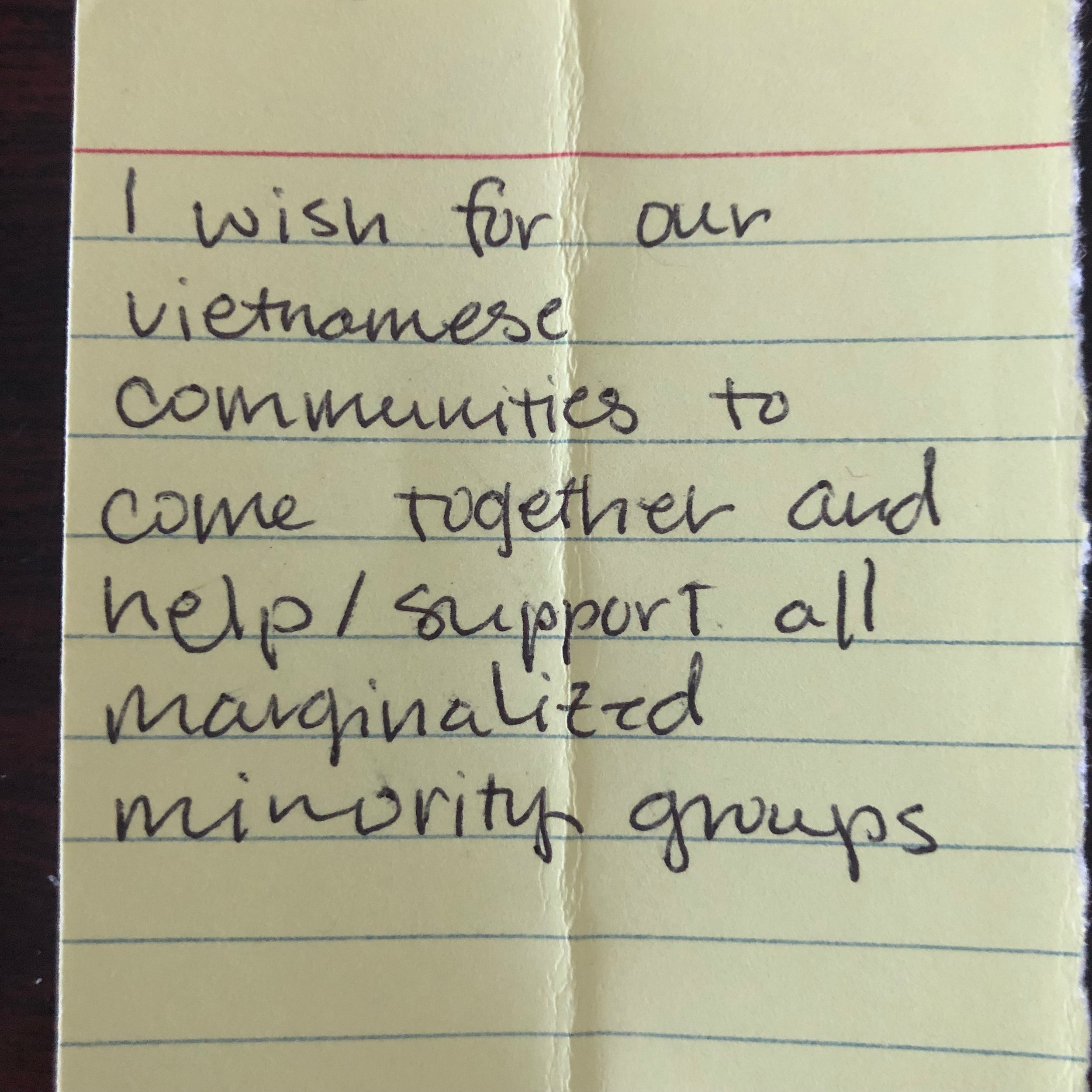

It's also blood soaked in the soil; poetry and song, weapons and war. It is every Olympic medal and flag raised over exultant faces. It is schoolchildren singing anthems and mouthing oaths. It is strangers gathering at coffee shops to drink and cheer. It is bumping into other people oceans away from the homeland, who speak as you do, who laugh at the same jokes, who ask the same questions. The community of people who imagine this truth are scattered, spiderwebbed across the world.

Perhaps the most bittersweet part is that the potential of our country is stunning. We have the people, the natural resources, the foundations of a history built on the ashes of an empire. And we waste it.

The West still remains under the sway of an enduring Judeo-Christian worldview and Greco-Roman philosophy, and that is unlikely to change anytime soon. For all their efforts at diversity and inclusion, most Americans have no idea what true diversity can look like, when it is not seeped in a narrative of apology and damage control.

In my childhood, I took for granted the balance we enjoy. Public holidays for Chinese New Year, Hari Raya Haji, and Deepavali; mother tongues integrated into school curriculum alongside Malay as the national language and English as our international tool; to be actively taught the history and significance of festivals from different cultures. I'm too used to our multiplicity, too naive in assuming that different cultures can mix and match, and that a compromise can be found in the cacophony.

We could have set a global example as a country with a moderate Islamic government and a multi-ethnic, multilingual society, one that lives tradition and progress apace.

I suppose this is the tragedy of it: corruption, laziness, confusion, a lack of education, censorship, power plays, fear, ignorance, the race card, and sometimes plain stupidity, from all quarters.

We live a reality that has not been fully explored, because there are those who choose dogmatism over a critical evaluation and acceptance of both our triumphs and our flaws. This waffling about our own history has impeded the shaping of a collective memory, and in turn has affected our ability to imagine ourselves a nation. Perhaps it is not for us to imagine a single, fixed, unmoving identity for our countrymen and -women. Perhaps we should embrace our heterogeneity more openly, and define ourselves by the constant shift and flow. That is still a long time coming.

Sometimes I think we have forgotten the worth of our democracy. It's been just over half a century and already we seem to have lost touch with what it means to rule ourselves, rather than let ourselves be ruled from afar. We have forgotten what freedom tastes like.

I see no easy solution here, only years of toiling against an embedded system that refuses to give. It's a fight that will take more vision and moral courage than anyone in the game has, right now. One must dream higher than that. Perhaps in another world I would give myself over to that, but not in this one, not today.

I live all the contradictions and paradoxes of my life. I am living in London but I am not English. I am ethnic Chinese but am not of China. I studied in Singapore without being Singaporean. I hold a Malaysian passport but am not bumiputera. I am none of these things but I am a part of them, as they are a part of me. And this is the identity I have carved out for myself in this postcolonial, post-globalised world: that I am a part of everything but am none of it, at the same time. There is no traditional ideal to live up to, no solidity beneath my feet. I must lay down the bricks one at a time, because there is no other path like mine, and only I can walk it. Home is not a place, a country, a person - it's the memory of something you hope to keep coming back to. It's not only what you make of it, but also what it makes of you.

Happy 60th, Malaysia.

--

Translations:

tanah air kita = our homeland. ‘tanah air’ literally translates to ‘earth and water’.

merdeka = freedom/independence. Malaysia's Independence Day is often referred to as Merdeka Day.

tapi = but/however, derived from the Malay word 'tetapi'

pulut = glutinous rice

suka = like/enjoy, shares the same spelling as the Malay word